Democritus, the next of the pre-Socratic philosophers in our History of Philosophy Refracted through Perfume series criticized Anaxagoras' explanation of qualities. Anaxagoras had hypothesized that the bits corresponding to the salient qualities of a thing are present in greater proportion than are the bits of other things. A bottle of Tom Ford Black Orchid contains a liquid which smells like Black Orchid because it is made up of many tiny little “Black Orchid” bits. His reasoning, to review, was in effect:

How could Black Orchid come from what is not Black Orchid, or Allure from what is not Allure?

The

atoms—as Democritus and his mentor, Leucippus, did in fact refer to

them—making up a perfume bottle are not tiny perfume bottles, or

even pieces of glass. Nor does the liquid inside comprise individual

“bits” sharing the qualities of the whole. Instead, the atoms are

altogether devoid of such sensorily perceivable qualities. We do not

perceive anything at all until the atoms have coalesced into much

larger congeries. Out of nothing, something comes. Where there were

no observable properties, suddenly they pop into our view, becoming a

part of our reality because they are experienced by us.

The

atoms have extension and shape, but they possess no qualities

perceivable by human beings through their sense organs alone. It is

only when the atoms are brought together in certain combinations and

proportions that such qualities arise, emergently, out of the

arrangements of individual atoms. Between the atoms is space.

Sound familiar? Yes, Leucippus and Democritus did indeed anticipate modern theories of chemistry, according to which all objects, including perfumes, comprise molecules, and all molecules are built up of atoms. Chemistry has obviously been refined over the more than 2,000 years since these pre-Socratic thinkers amazingly hit on something like it by casting about in an aim to understand the world in which they found themselves. We now identify the atoms in question as Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, etc. The early atomists knew nothing about the scientifically hypothesized atoms of the nineteenth and twentieth century. Was it just a lucky guess, a stab in the dark? My hunch is that their bold conjectures were based on their first-hand experience of perfume.

Sound familiar? Yes, Leucippus and Democritus did indeed anticipate modern theories of chemistry, according to which all objects, including perfumes, comprise molecules, and all molecules are built up of atoms. Chemistry has obviously been refined over the more than 2,000 years since these pre-Socratic thinkers amazingly hit on something like it by casting about in an aim to understand the world in which they found themselves. We now identify the atoms in question as Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, etc. The early atomists knew nothing about the scientifically hypothesized atoms of the nineteenth and twentieth century. Was it just a lucky guess, a stab in the dark? My hunch is that their bold conjectures were based on their first-hand experience of perfume.

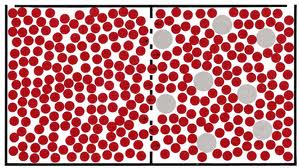

Perfumes which look empirically indistinguishable often smell wildly different. How to explain this disparity in perception? The problem with Anaxagoras' theory was that all things were said to be made up of things which they resemble. This does not help in explaining the distinction in smell between two liquids of the same color.

Take some perfumes by Annick Goutal with similar shades of color, say Quel Amour, Eau d'Hadrien, and Petite Chérie. These perfumes smell radically different. What makes these perfumes distinct, despite their visual similarities, is not that they comprise tiny bits of, respectively, Quel Amour, Eau d'Hadrien, and Petite Chérie.

Why, again, do beautiful, fully composed perfumes comprising high-quality materials, such as Miller Harris Jasmin Vert or Géranium Bourbon or Figue Amère smell so different from a vat-produced chemical soup which induces dread and malaise in the wearer? (The selection of examples is left as an exercise for the reader.) It is not because the former are made up of tiny homuncular (so to speak) bottles of great perfume. No, something else must be going on, the atomists correctly inferred.

True,

one can dig deeper, if one wishes, but theories of multidimensional

strings are not going to provide much insight in attempting to

understand why when an ebay hawk or grey market decanter dilutes a

perfume it smells weaker than it did before. We modern people pretty

much call it a day at the level of chemistry, which helpfully

explains all sorts of empirical phenomena readily observable by us.

Colligative

properties such as freezing point depression and boiling point

elevation are good examples. Why does making a sorbet with a touch of

alcohol added yield a softer outcome than a sorbet mixture to which

no alcohol is added? Why does pouring salt on the sidewalk in

wintertime prevent ice from forming?

We can even understand in the basic concepts of organic chemistry why trans-fats are worse than cis-fats. Chemistry offers satisfying answers to these questions. Digging deeper is possible, and physicists certainly do that when they go to work in their laboratories, but good luck trying to grapple with aspects of everyday existence—becoming—through appeal to strings. You may as well just return with Parmenides to the realm of Being!

Where there was no Jean Patou 1000, suddenly it appeared, in a grand creation act, as though plucked from a magician's hat, when an assortment of atoms (in molecules) were juxtaposed in just the right way and in the right proportions. That's pretty much all that we need to know, and all that perfumers need to know as they scrupulously document their new formulas so that it will be possible in the future, to reproduce over and over again—should anyone choose to do so—the final combination of ingredients which make up what has been christened a new perfume.

Democritus

was a materialist interested in mechanical explanations of phenomena.

He was a “How?” man, not a “Why?” man. For this reason, some

historians have considered him to be more of a protoscientist than a

philosopher. In fact, his predilection for mechanical explanations

was itself a philosophical position, in some ways anticipatory of

modern pragmatism. What works is valid, and what does not work is

invalid. That is the essence of pragmatism, in a nutshell. And it

rings true for perfume as well.

An

iconic perfume has succeeded in carving out a new spot of previously

uncharted territory on the grand olfactory map. A second requirement,

for even a highly original perfume to achieve true icon status, is

that it enjoy widespread market success. Many perfumes carve out new

spots of previously uncharted territory, but for one reason or

another they are market flops. Usually they are discontinued. Only

iconic perfumes hit on a formula which appeals to a sufficient number

of consumers to warrant keeping the perfume in production. But the

contribution of the house, its willingness and ability to market the

perfume is even more important to contemporary recognition than is

the nature of the creation itself. The Britney Spears perfume collection has reaped millions upon millions of dollars of profits.

|

Curious, Fantasy, In Control Curious, Midnight Fantasy,

Believe, Curious Heart, Hidden Fantasy, Circus Fantasy

(Not Pictured: Radiance and Cosmic Radiance)

|

Materialism

and Hedonism

The

retention of the same name for what has become a different perfume,

as in the case of Guerlain Mitsouko,

or the preposterous renaming of Miss

Dior Chérie

as Miss

Dior,

may on its face

appear to provide confirmation of the Parmenidean view on the realm

of becoming, that it is the realm of falsehood and illusion. Then

again, Yves Saint Laurent Champagne

was also renamed, to Yvresse,

not because of a blunder on the part of some officious executive

wishing to leave his grimy fingerprints on the perfume, but because

of a testy dispute with French champagne makers over what they took

to be the inappropriate use of that term.

Everything is fair game in the realm of becoming, and people will do what they will do in order to get what they want. But if all acts of naming are a matter of convention, then is anyone really to blame for retaining the name of a formerly great perfume and using it to label a less noble variant of the same? Whatever works, works. What does not work, does not work. We find ourselves, my fragrant friends, yet again, in the realm of Parmenidean tautology, now in the service of an eminently non-Parmenidean philosophy!

Everything is fair game in the realm of becoming, and people will do what they will do in order to get what they want. But if all acts of naming are a matter of convention, then is anyone really to blame for retaining the name of a formerly great perfume and using it to label a less noble variant of the same? Whatever works, works. What does not work, does not work. We find ourselves, my fragrant friends, yet again, in the realm of Parmenidean tautology, now in the service of an eminently non-Parmenidean philosophy!

In

a materialist world view such as that of Democritus and the atomists,

everything, including morality, is a matter of convention. There is

no higher power; there are no laws written in invisible ink in the

sky; and there is no afterlife—whether filled with heavenly bliss

or eternal damnation. What you see—or sniff—here and now, on

planet earth, is what you get.

In

this sort of world view, materialistic hedonism, there is no pure and

absolute, immutable essence or Platonic Form of Perfume (to

anticipate a bit future episodes of this lengthy story...). No,

perfumes are short-lived, fragile creations, creatures of sorts, kept

in existence only for so long as they prove to be profitable to

someone somewhere. It's not enough that a perfume once launched be loved; it must

also earn its right to continue to exist.

Once

a perfume has ceased pulling its weight, so to speak, perfume houses

simply pull the plug. From the hard-headed perspective of

pragmatically oriented materialists, vain attempts to re-create the perfumes of centuries past are futile efforts to change the structure

of reality as conceived by naturalistically minded thinkers such as

the atomists of ancient Greece.

One

interesting implication of a hedonistic picture of perfume

appreciation—such as seems clearly to be implied by the atomism

championed first by Leucippus and Democritus, and later by Epicurus

(who, too, will be discussed in more detail in a future

episode...)—may be that many perfumistas, in their enthusiasm to

exalt perfumery as an art, give short shrift to the impact of

marketing on our reception of perfume.

This picture lends weight to the idea, discussed in The Bottle Controversy, that the vessel in which a perfume is housed and travels and from which perfume is drawn, being a sensorily perceived object, is no less worthy of our attention because it is no less capable of producing pleasurable sensations in us. The question becomes: in terms of the overall pleasure derived, is the bottle less important than the scent inside? While it is true that the bottle can lead one deceptively to buy a perfume which does not deliver on the promise of its packaging, the same can be said of advertising more generally. In fact, that is what advertising is: seduction, pure and simple. Do you really need that item or gadget—or bottle? Advertising has as its aim to convince you that you do.

There is a substantive sense in which the bottle contributes to the overall success of a marketing campaign. But there is a difference: the bottle is an independent object, designed by someone somewhere no less than was the perfume, and therefore potentially worthy of our regard. It, too, exists to our sensory organs because a group of atoms and molecules have been brought together and arranged in a particular way so as to affect our sensory receptors. When the sight or touch of a bottle provides pleasure, then it has just as much value as any other source of pleasure, including the scent of perfume.

That, at any rate, my fellow fragrant travelers, is the way in which the ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus appears to have viewed these matters.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All relevant comments are welcome at the salon de parfum—whether in agreement or disagreement with the opinions here expressed.

Effective March 14, 2013, comment moderation has been implemented in order to prevent the receipt by subscribers of unwanted, irrelevant remarks.